Image source: http://www.admadness.co/

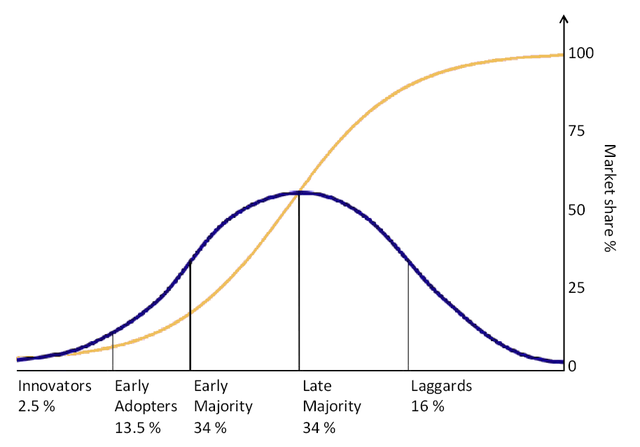

You may be asking yourself, “This research around adoption curves is all fine and interesting but how does it apply to digital marketing?”

Great question. Let’s walk through it with a real-world example from Apple.

Apple’s Brand Ecosystem

Rogers outlined five characteristics that influence a person’s decision to adopt or reject an innovation.

Here’s how Apple plays off this brilliantly (From Diffusion of Innovations).

- Relative Advantage – How improved an innovation is over the previous generation.

For example, is the new iPad that much better than the previous? Over a laptop? Over a Microsoft or Amazon product? - Compatibility – The level of compatibility that an innovation has to be assimilated into an individual’s life.

In short, how hard is it to integrate this into my daily life? An iPod is very easy to integrate as Steve Jobs famously said when introducing it to the world, “A thousand songs in your pocket.” - Complexity – If the innovation is too difficult to use an individual will not likely adopt it.

Consider touchscreen interfaces vs. multiple menus: We’re in a hurry. We’re lazy. We don’t want to think. Tap a button and experience an app – an iPhone is so intuitive toddlers can quickly use them. - Trialability – How easily an innovation may be experimented with as it is being adopted. If a user has a hard time using and trying an innovation this individual will be less likely to adopt it.

Is there a sandbox to try it out in first? Think of the Apple retail store experience which is specifically designed to get users interacting with all the devices in a casual way. - Observability – The extent that an innovation is visible to others. An innovation that is more visible will drive communication among that person’s peers and personal networks and will in turn create more positive or negative reactions.

Consider the ubiquitous white headphones that drove the original print campaign for Apple and showed off to the world how that person was listening to an iPod.

Twitter’s Adoption vs. Awareness paradox

Note: Awareness and adoption are two distinct metrics and it’s important as a digital marketer not to confuse the two.

While awareness is important, it is adoption of a solution that drives an economic engine as it can be monetized. People can know about an iPod but it’s the act of them adopting the device into their lives by buying the product and content on iTunes that makes Apple so profitable.

It’s also worth noting that adoption can mean many things in digital – subscribing to an email newsletter, liking a brand on Facebook, following on Twitter/Instagram, or grabbing an RSS feed. It’s more commonly referred to as “engagement” and we’ll cover the nuances of this later in the Strategy and Measurement sections.

If we look at the research, we see that Twitter had some serious challenges for adoption.A staggering 92% of Americans were aware of the platform, so it obviously no longer had to worry about getting the word out about the brand.Interestingly, an almost complete saturation of the US market for brand awareness puts it in the enviable ranks of household names like Nike or Coca Cola in 2011.